on

Climb from the Valley and Descend from the Peak

I’m here to tell you what your sycophantic chatbot won’t. You are probably wrong about AI. This is not me talking down to you. I’m probably wrong too.

I want to tell you a particular way in which I’m often wrong, which I suspect might be getting you too. You look at the world today, then layer what you know about AI on top, then make an assessment about what will be.

For example, you might look at a call center, layer on your experience talking to AIs, and determine that call centers will be composed exclusively of robots. Or you see how painful it is to fill in some paperwork, perhaps some permitting with the local government, and think that AI will surely be able to make that easier. And it will. Just like calculating the slope of a curve, in the short term, the current direction is a pretty good predictor.

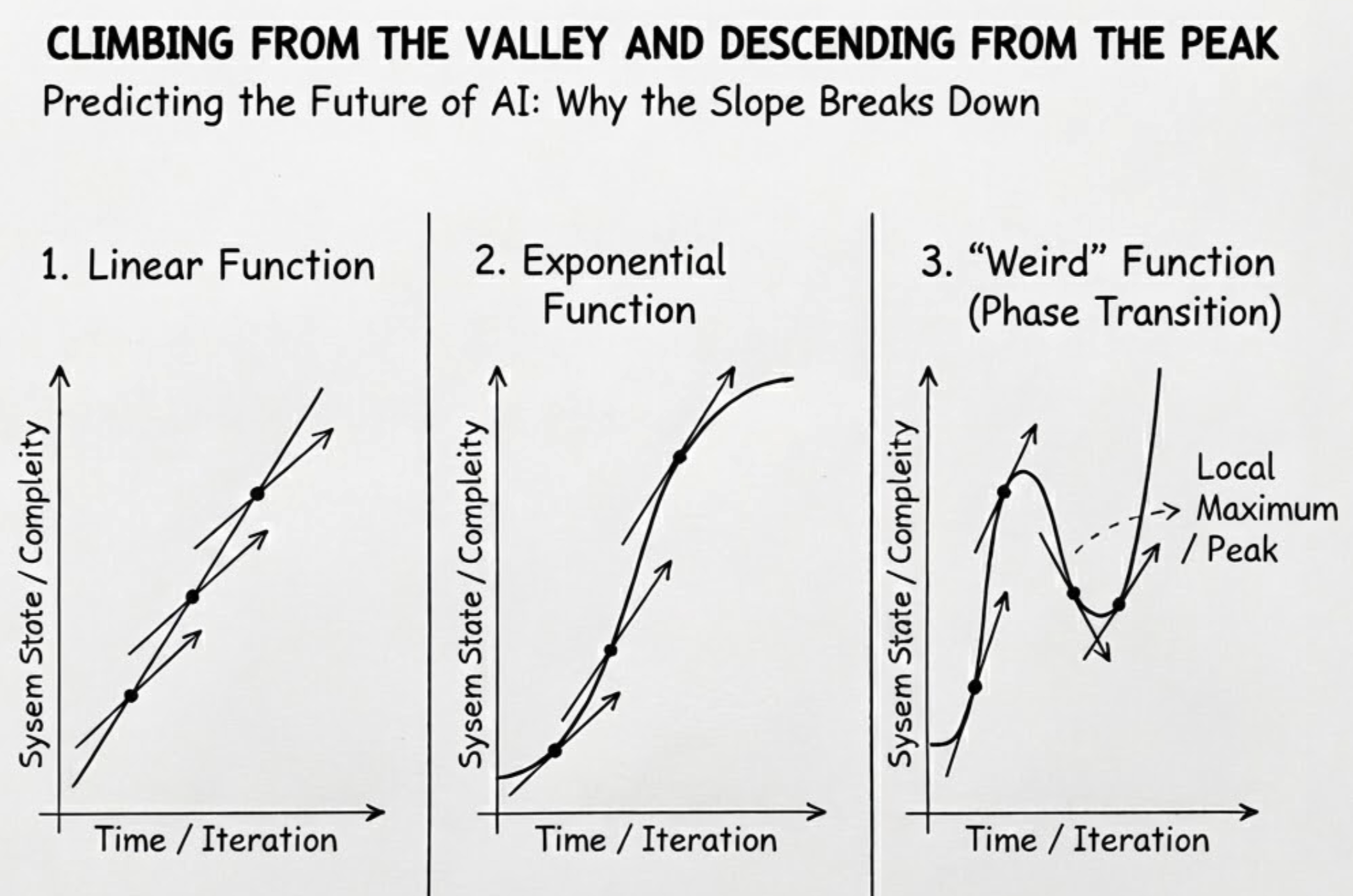

But iteratively calculating the slope won’t reconstruct a function. This is more true when the function is more surprising. A linear function can be fully predicted by a single slope calculation. An exponential takes more samples, but eventually you get the gist. But add more complexity and you are toast.

I believe AI is introducing the sort of complexity that prevents us from seeing the future by putting a foot in front of the other.

I want to share a different technique for visualizing the future. This is not the kind of technique that will make you rich. We are talking about a vanishing mirage seen through a lysergic squint. But I claim that if you practice this technique and then go to sleep for 10 years, you’ll be less surprised when you wake up.

Predicting a weird function by taking one step at a time is hopeless. But there’s a trick: if you can guess where a local maximum might be, you can work backward from there. You won’t know the exact path, but you’ll have a better sense of the terrain than if you just kept walking forward blind.

We don’t have an oracle of the future. But we can do something similar: imagine an extreme version of the future where AI is fully saturated, maximally capable, and nearly free. Then walk backward, asking what still makes sense.

Let’s go back to call centers. We replace people with AI agents. Now we transport to the future, the chatbots get really really good, and really really cheap. They can solve any problem anyone calls with, better than any human. They don’t only receive calls, they can make them too. They can proactively reach out to other humans to accomplish a task.

These agents can both respond to calls as well as make calls. Why should a human be at either side of these conversations? Let’s imagine that far future for a second where every business-oriented phone call (reservations, troubleshooting, etc) has AIs on both ends. Now walk backward. What do these AIs talk about? Do they offer a menu of options to each other? Do they exchange pleasantries? Do they threaten each other with lawyers? Maybe, but it’s unlikely those conversations are anything like those we have today.

Hmmm. Why would these agents make phone calls at all? Why talk to each other using voice when they could just exchange text? But wait, why would they have to talk at all in many cases? If my AI is 100% diligent and will always get refunds for me when the airline fucks up, why wouldn’t the airline agent just always refund me automatically? That saves us both trouble and we know what the other equilibrium looks like. The other equilibrium is an endless escalation of more inbound calls, and more minutes listening to elevator music, but neither of our AIs care. The friction is gone. The problem has changed. The future is not what we initially thought.

Governments are slow, so they need to dampen the influx of requests: construction permits, civil disputes, 911 calls. It’s generally not tasteful for the government to manage citizenry demands using basic supply and demand methods, such as price discrimination. Want to skip the DMV line? Pay 10x for your ID. So they achieve the same thing indirectly. One of those methods is making processes more burdensome, which means they often require professional assistance, which makes them more expensive, which has a similar effect without the government directly taking higher payments from richer, more motivated residents. This burden usually takes the form of longer, more complex paperwork.

But now my AI can do paperwork, so the government gets slammed with all sorts of demands, like FOIA requests. Now the government buys AI to manage the inbound requests. But neither the government AIs, nor those incoming, care about the length and complexity of a form. Hence the whole notion of complexifying process stops having a purpose. What might happen? Well, the government might have to actually start making use of price discrimination. Or maybe there is a marketplace of government credits, where we all get a certain amount per year, but we can sell them to each other.

But just like we won’t have a world in which AIs talk to each other over the phone for eternity, we will probably not have a world where AIs are playing a cat and mouse game for complexifying processes. If anything, the process will become simpler, use the least amount of compute, and arrive at a resolution quickly.

You get the pattern now. College applications: what happens when it’s just AIs talking to each other? Why not just have my AI predict what college I might be able to get into, and the college AIs study my paper trail to predict if I’m worthy? Why not get ahead of the issue and send the most desirable high-schoolers automatic acceptance before they apply? Job applications, same thing. The whole ritual dissolves.

This doesn’t mean you can’t build a business today that uses AIs to help college applicants, or one that helps universities screen those applications. You might make good money. But while you’re at it, climb to the peak and look around.