on

Portfolio Simulator

This document is intended to help those interested in venture capital reason about expected fund-level returns. All multiples are net to LPs (i.e. after fees and 20 % carry) unless noted. I wrote this originally in 2023, and updated it in April 2025 with about 60 min of vibe coding.

I took data from this 2020 report (page 14), and filtered it for the 10 year period between 2004 and 2013. I chose that period because the vintages surrounding the internet bubble show unusually high volatility, and discarded years closer to 2020 given that it takes about 7 years for the TVPI to stabilize. I also used Angel List to estimate some of the higher percentiles, although the time period for this data is unclear.

Cambridge Associates 10-yr TVPI (2004-2013)

| Vintage | Pooled | Mean | Median | Upper Q | Lower Q | Funds |

| ------- | ------ | ---- | ------ | ------- | ------- | ----- |

| 2004 | 1.69 | 1.72 | 1.2 | 1.82 | 0.82 | 63 |

| 2005 | 1.68 | 1.66 | 1.41 | 2.07 | 0.91 | 61 |

| 2006 | 1.69 | 1.56 | 1.59 | 1.95 | 0.75 | 78 |

| 2007 | 2.29 | 2.38 | 1.76 | 2.93 | 1.31 | 68 |

| 2008 | 1.77 | 1.71 | 1.4 | 2.21 | 1.09 | 64 |

| 2009 | 2.1 | 2.12 | 1.75 | 2.46 | 1.3 | 23 |

| 2010 | 3.21 | 2.8 | 2.12 | 3.41 | 1.41 | 48 |

| 2011 | 2.48 | 2.26 | 1.9 | 2.71 | 1.39 | 44 |

| 2012 | 2.21 | 2.48 | 1.73 | 2.37 | 1.35 | 55 |

| 2013 | 2.02 | 2.01 | 1.81 | 2.26 | 1.34 | 59 |

| Average | 2.11 | 2.07 | 1.67 | 2.42 | 1.17 | 56 |

Angel List Fund Performance Calculator (April 2025)

| Percentile | Net IRR |

| ---------- | ------- |

| 90th | 35% |

| 95th | 40% |

| 99th | 55% |

Core assumptions

- Fund size $50 M — prototypical seed/Series A vehicle

(Fund size is implicit; all multiples are net-to-LP.) - Fee load 15 % lifetime (≈ 2 % per year for 7-8 years, charged up-front)

- Carry 20 % GP promote on profits after fees

- Initial cheques 22 equal-sized first investments, no follow-ons — keeps the portfolio math clean

- Deal-outcome model

- 55 % outright zeros (0×)

- 45 % survivors drawn from LogNormal (μ = 1.10, σ = 1.40), capped at 200×

↳ Continuous returns smooth the histogram and anchor the 95 th percentile near ~6×.

- Capital calls 25 % of committed capital in each of years 0-3 — mirrors common pacing

- Exit timing Each company realises its full value in a single lump-sum exit uniformly between years 4-10 — spreads cash flows for a realistic IRR profile

- IRR calculation Exact cash-flow schedule solved with

numpy_financial.irr— no midpoint shortcuts - Reproducibility Fixed NumPy RNG seed 2025; 3 500 simulated funds — rerun and you’ll get identical tables and plots

Simulated Results

| Percentile | Sim TVPI | Sim IRR % |

| ---------- | -------- | --------- |

| 25th | 1.45 | 5.6 |

| 50th | 2.09 | 12 |

| 75th | 3.16 | 20.7 |

| 90th | 4.6 | 30.7 |

| 95th | 5.85 | 38.6 |

| 99th | 8.31 | 55.8 |

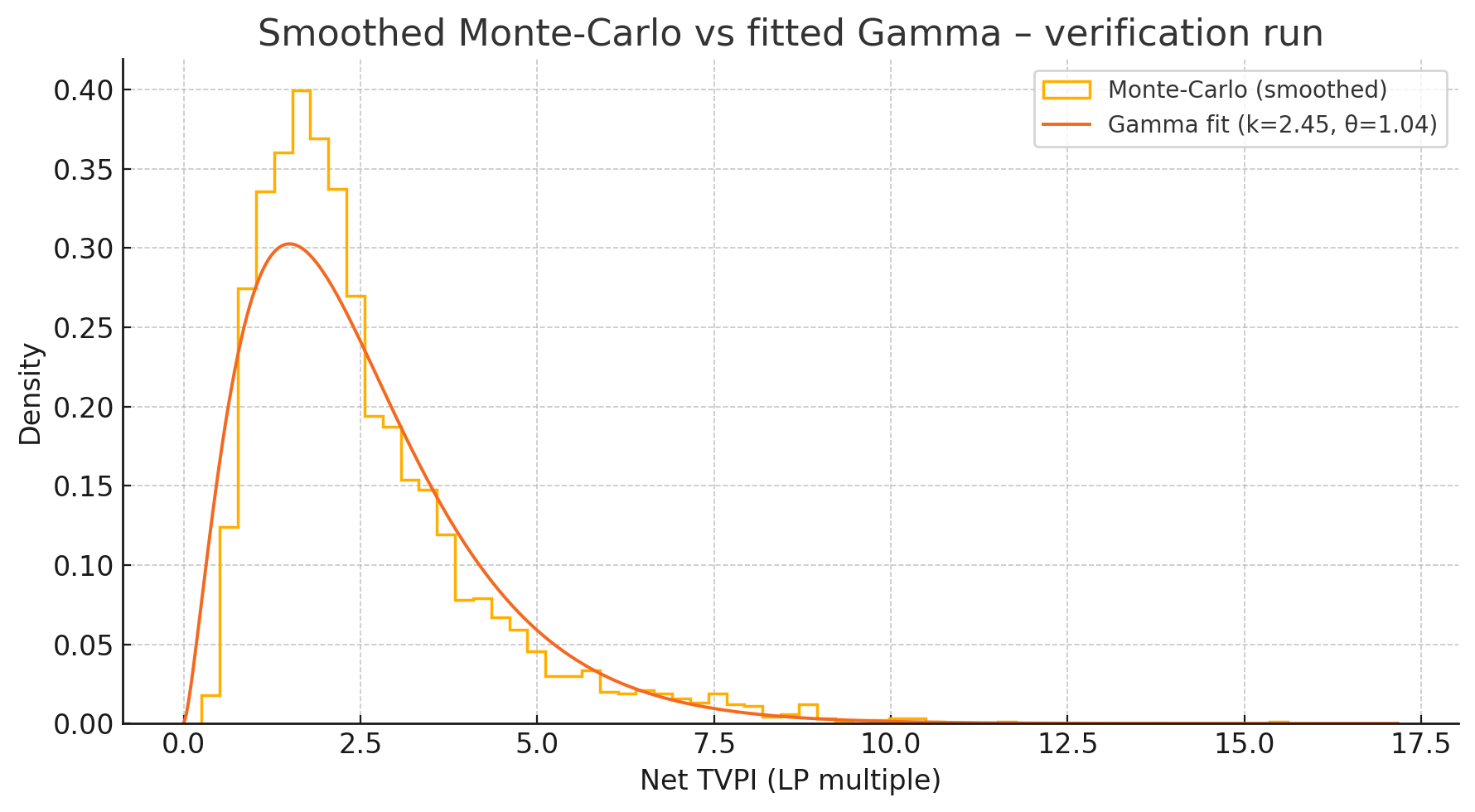

We fit a Gamma distribution to the Monte-Carlo TVPI sample after the simulation finishes. Overlaying this analytic curve serves two purposes: first, it provides a quick visual check that the simulated histogram has the expected shape, and second, it gives readers a neat closed-form PDF and CDF they can drop into their own spreadsheets without rerunning thousands of Monte-Carlo draws.

Code

"""

Smoothed Venture-Fund Monte-Carlo Simulator

==========================================

This script generates a continuous, log-normal–based deal-level simulation

that matches target fund-level TVPI percentiles, then:

• Computes IRRs with an explicit cash-flow schedule

• Prints a Markdown-formatted percentile table (TVPI + IRR)

• Plots the Monte-Carlo histogram with a moment-matched Gamma overlay

Best-fit parameters were hand-picked from a prior grid search and are

hard-coded here, so there is **no grid search** on execution.

Author : Ivan Bercovich (April 2025)

License: MIT

"""

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

# 1. Imports

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

import numpy as np

import numpy_financial as npf # IRR solver

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import math

import tabulate

from textwrap import indent

# NB: matplotlib uses your active backend; no style tweaks applied to keep

# portability high.

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

# 2. Global settings (purely reproducibility + model inputs)

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

SEED = 2025 # deterministic RNG seed

N_FUNDS = 3_500 # Monte-Carlo fund draws

N_INVEST = 22 # equal-size first cheques (no follow-on)

# ---------- Deal-outcome model ---------- #

# “Fail” cheques return 0×.

# “Survivors” follow a single *log-normal* distribution, truncated to cap

# pathological outliers (>200× is exceedingly rare in seed funds).

P_FAIL = 0.55 # probability a cheque is a total write-off

MU_LN = 1.10 # log-mean (in ln-space) of survivor multiples

SIGMA_LN = 1.40 # log-std-dev of survivor multiples

MAX_MULT = 200.0 # hard cap on extreme successes

# ---------- Fund economics ---------- #

MGMT_FEE = 0.15 # lifetime management fees (15 % of committed)

CARRY = 0.20 # GP carry on profits (standard “80 / 20” split)

# ---------- Exit-timing logic ---------- #

EXIT_YEAR_MIN = 4 # earliest exit

EXIT_YEAR_MAX = 10 # latest exit

# A single lump-sum distribution is drawn uniformly in [4, 10].

# ---------- Targets for reference ---------- #

TARGET_TVPI = np.array([1.25, 2.0, 2.75, 5.0, 6.5, 8.0]) # 25–99 th

PERCENTILES = [25, 50, 75, 90, 95, 99]

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

# 3. Helper functions

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

def draw_survivor_returns(size: int, rng: np.random.Generator) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Draw `size` log-normal multiples and cap them at `MAX_MULT`.

Parameters

----------

size : int

Number of survivor cheques to simulate.

rng : np.random.Generator

Numpy RNG instance for reproducibility.

Returns

-------

np.ndarray

1-D float array of length `size`, each ≥ 0.01 × and ≤ MAX_MULT ×.

"""

draws = rng.lognormal(MU_LN, SIGMA_LN, size)

return np.clip(draws, 0.01, MAX_MULT)

def simulate_fund_tvpi(rng: np.random.Generator) -> float:

"""

Simulate one fund’s **net-to-LP TVPI**.

Steps

-----

1. Sample failures vs survivors for each of `N_INVEST` cheques.

2. Draw continuous survivor returns.

3. Take the arithmetic mean ⇒ gross TVPI (all cheques equal size).

4. Convert gross ⇒ net by subtracting fees and applying carry.

Returns

-------

float

Net TVPI (multiple of distributed / committed capital).

"""

# 1) Boolean mask of failures

fails = rng.random(N_INVEST) < P_FAIL

n_survivors = (~fails).sum()

# 2) Continuous survivor multiples

survivor_mults = (

draw_survivor_returns(n_survivors, rng) if n_survivors else np.array([])

)

# 3) Portfolio gross multiple (simple mean; failures contribute zero)

gross_tvpi = survivor_mults.sum() / N_INVEST

# 4) Net to LPs: LP capital is reduced by mgmt. fee, and GP takes 20 % carry

net_tvpi = (1 - MGMT_FEE) * (1 + (1 - CARRY) * (gross_tvpi - 1))

return net_tvpi

def fund_irr(tvpi: float, exit_year: int) -> float:

"""

Compute an internal rate of return given:

• `tvpi` – net multiple (already net of fees & carry)

• `exit_year` – year in which *all* gains are realised

Capital calls: –25 % in each of years 0, 1, 2, 3.

"""

calls = [-0.25] * 4 # negative cash flows

cfs = calls + [0] * (exit_year - 3) + [tvpi]

return npf.irr(cfs) # returns decimal (e.g. 0.15 ⇒ 15 % IRR)

def markdown_table(df: pd.DataFrame) -> str:

"""Return a DataFrame rendered as GitHub-flavoured Markdown."""

return df.to_markdown(index=False, tablefmt="github")

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

# 4. Monte-Carlo simulation

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

rng = np.random.default_rng(SEED)

# ---- Run the fund loop ---- #

tvpi_mc = np.array([simulate_fund_tvpi(rng) for _ in range(N_FUNDS)])

# ---- Assign a random exit year per fund ---- #

exit_years = rng.integers(EXIT_YEAR_MIN, EXIT_YEAR_MAX + 1, N_FUNDS)

irr_mc = np.array(

[fund_irr(m, yr) for m, yr in zip(tvpi_mc, exit_years)]

) * 100 # convert to %

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

# 5. Summarise results in Markdown

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

summary_df = pd.DataFrame({

"Percentile": [f"{p}th" for p in PERCENTILES],

"Target TVPI": TARGET_TVPI,

"Sim TVPI": np.round(np.percentile(tvpi_mc, PERCENTILES), 2),

"Sim IRR %": np.round(np.percentile(irr_mc, PERCENTILES), 1),

})

print("\n### Monte-Carlo Results (Markdown table)\n")

print(markdown_table(summary_df))

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

# 6. Fit a Gamma distribution for visual overlay

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

mu, var = tvpi_mc.mean(), tvpi_mc.var()

shape_g = mu**2 / var # k

scale_g = var / mu # θ

# Analytical Gamma PDF for plotting

x = np.linspace(0, tvpi_mc.max() * 1.1, 500)

pdf_gamma = (

x ** (shape_g - 1) * np.exp(-x / scale_g)

) / (math.gamma(shape_g) * scale_g**shape_g)

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

# 7. Plot histogram + Gamma overlay

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

plt.figure(figsize=(9, 5))

plt.hist(

tvpi_mc,

bins=60,

density=True,

histtype="step",

lw=1.25,

label="Monte-Carlo (smoothed)",

)

plt.plot(

x,

pdf_gamma,

lw=1.4,

label=f"Gamma fit (k={shape_g:.2f}, θ={scale_g:.2f})",

)

plt.xlabel("Net TVPI (LP multiple)")

plt.ylabel("Density")

plt.title("Smoothed Monte-Carlo vs fitted Gamma")

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

# 8. Print key simulation settings (optional provenance block)

# --------------------------------------------------------------------------- #

print("\n--- Simulation parameters -------------------------------------------")

print(

indent(

f"""

Funds simulated : {N_FUNDS}

Cheques per fund : {N_INVEST}

Failure probability : {P_FAIL:.0%}

Survivor log-normal μ : {MU_LN:.2f}

Survivor log-normal σ : {SIGMA_LN:.2f}

Management fee (lifetime) : {MGMT_FEE:.0%}

Carry : {CARRY:.0%}

Exit year distribution : Uniform [{EXIT_YEAR_MIN}, {EXIT_YEAR_MAX}]

RNG seed : {SEED}

""".strip(),

prefix=" ",

)

)